Behind the word "Troubles" in the British history book: 30 years of blood and hate in Northern Ireland conflict

Belfast in those thirty years was very different from other cities in Europe. There are heavily armed military vehicles on the streets, soldiers armed with live ammunition are ready to attack at any time, police stations need to be protected by high-wall wire grids, walls are built between adjacent streets, roadblocks are set up outside commercial areas to prohibit vehicles that may contain explosives from entering and leaving, and people who buy daily necessities outside shops queue up to pass the security check. Bombings and shootings are one after another, and people in other parts of Britain are also fearful, because they don’t know which car, which trash can and which forgotten backpack will suddenly detonate. At that time, there was a chilling name: Irish Republican Army.

Origin: religious struggle, civil rights parade turned into violent conflict

The conflict between Northern Ireland and Ireland is a territorial conflict, a conflict between the ownership and identity of two completely different groups, which has both political and religious factors. Since the 16th century, many immigrants from England and Scotland moved to northern Ireland. Most of them were wealthy Protestants, pushing the original Catholics in Northern Ireland to the edge. In 1801, Ireland became a part of the United Kingdom, but like Scotland, some people’s calls for independence never stopped. In 1916, the predecessor of the Irish Republican Army launched the "Easter Uprising" in Dublin, and Irish nationalism was high. In 1919, Sinn Fein (meaning "ourselves") and the Irish Republican Army were founded with the goal of fighting for independence. In 1920, the British government established two houses in Ireland, the North and the South, which were in charge of the 26 counties in the south and the 6 counties in the north, giving them some autonomy. In 1921, Britain and Ireland signed an agreement to establish a free state, and 26 counties in the south became independent from the United Kingdom. In 1937, the Free State declared the establishment of the Republic of Ireland.

Six counties in Northern Ireland remained in Britain because of years of immigration, when Protestants accounted for the majority of the population in Northern Ireland. Protestants don’t want to leave England, so they are also called royalists or unionists; Indigenous Catholics, on the other hand, hope to be unified with the south, so they are also called Republicans or nationalists. The conflict between the two factions has been constant, but it has not reached the point of white-hot later. Although defense diplomacy is still dominated by London, the Northern Ireland House is still relatively autonomous. For decades, the Northern Ireland House has been controlled by The Ulster Unionist Party——UUP), which marginalized Catholics from employment, education, medical care and health care. Catholics are discriminated second-class citizens.

Where there is oppression, there is resistance. The civil rights movement that began in the United States in the 1960s spread to Northern Ireland, and Northern Ireland Catholics took to the streets to demand more political rights, social supply and cultural recognition, but these were resisted by Protestants. In October 1968, the demonstrations demanding civil rights quickly turned into violent conflicts, and the police controlled by royalists were extremely heavy, and various contradictions also intensified rapidly. The royalists and Republicans were at loggerheads. This is the beginning of the "Troubles" defined in the history books.

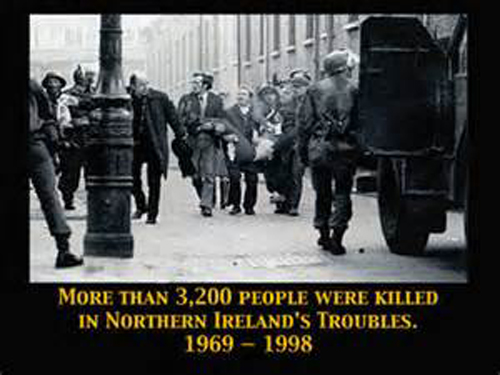

Confrontation: 3,600 British troops were killed and 50,000 wounded.

Seeing that the Irish Parliament could not control the situation, the London government sent troops to Northern Ireland to maintain order in 1969. Although the British army set foot on the land of Northern Ireland, most ordinary people could accept it, but a small number of extreme Republicans were quite disgusted. The civil rights demand that should have been reformed within Northern Ireland quickly rose to the movement of separation from Britain and reunification with the south. In the same year, some extremists in the Irish Republican Army separated and established the Provisional Irish Republican Army, which is also known as IRA. They began to directly attack the British army and announced that they would carry out a "protracted war" against Britain and the royalists.

The British government took a tough approach to IRA at first. In 1971, they announced internment’s policy that they could be detained without trial, and more than 2,000 people were arrested. On January 30, 1972, 10,000 people staged a demonstration demanding civil rights in Delhi, London, Northern Ireland. The procession clashed with British troops maintaining order, and soldiers shot and killed 13 people and injured 13 others. This was "Bloody Sunday". The hatred of all parties intensified, and the London government decided to cancel the completely paralyzed Northern Ireland House, take the management power back to the central government in an all-round way, and set up a full-time Secretary-General for Northern Ireland to manage it.

Instead of killing IRA, the British government’s tough measures made it stronger and more morale. Young Catholics actively participated in IRA. They were financially supported by Irish immigrants from the United States, with better weapons and more professional means. Car bombs and plastic bombs were used, and shooting was more common, and the death toll soared.

For example, in July 1972 alone, there were nineteen explosions in Belfast. IRA has also extended its military activities originally limited to Northern Ireland to Britain and Europe, making people in Britain fearful. To give a few examples, in February 1972, the Aldershot bombing in Britain killed seven people. In September 1973, London’s King’s Cross and Euston railway stations were bombed, and 21 people were injured; In February 1974, a bus exploded on the expressway, killing 12 people; In June 1974, the British House of Representatives exploded, causing extensive damage to the House building and injuring eleven people. In October 1974, Guildford Bar exploded, killing five people and injuring 44 others. In November, 1974, the Birmingham Bar exploded, killing 21 people and injuring 182 others.

When people talk about the conflict in Northern Ireland, they always think that IRA is the culprit, but it is not entirely true. Royalists are not soft either. They have set up armed forces one after another, such as UDA(Ulster Defence Association) and UFF(Ulster Freedom Fighter), which were established in September 1971. They imported guns and ammunition from South Africa, attacked Catholic residential areas and bombed bars and public places where Catholics gathered, in the same way as IRA.

Therefore, the 30-year "Troubles" in Northern Ireland was a civil war between Republicans and royalists. The police and British troops tried to maintain peace in the war, and sometimes they went off accidentally, hurting innocent people. Republicans also accused the police of conspiring with British troops and royalists’ armed groups. Hatred is growing, society is more isolated, and the economy is paralyzed.

Intensified: Prisoner hunger strike Margaret Thatcher tough

There is no improvement in political negotiations, and the violent actions of the Irish Republican Army and the royalist armed forces continue. On March 1, 1981, Bobby Sands, an IRA prisoner in Metz Prison in Belfast, began a hunger strike, demanding that the British government regard them as "political prisoners" rather than terrorists or ordinary murderers. During the hunger strike, many prisoners joined in stages. However, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s attitude was quite tough, and she flatly refused the hunger strikers’ demands. Thornton died after 66 days of hunger strike. The Iron Lady made no apologies in her speech in the House of Representatives. She said that if she made concessions to IRA prisoners, she would give them a license to slaughter innocent people. Seven months later, the prisoners stopped their hunger strike automatically, but more than a dozen IRA members had starved to death.

The British media regarded the cessation of the hunger strike as a victory for Thatcher’s government, but they didn’t know that her tough attitude attracted more explosions and shootings. Margaret Thatcher’s handling of the hunger strike was like the detention without trial in 1971 and the bloody Sunday in 1972. The more the government resorted to coercion, the more young people took part in IRA, the higher their morale, the fiercer the armed conflict and the more divided Northern Ireland. In July 1982, in Hyde Park and Ruijin Park in London, two bombs of IRA exploded at the celebration ceremony of the British army, killing four British soldiers, seven members of the military band and seven military horses. On October 12, 1984, the Brighton bombing was aimed at assassinating Mrs. Thatcher. Although the Iron Lady survived, five people died, including her two political allies. On November 8, 1987, the Enniskillen bombing killed eleven people and injured sixty-three. The bombing made IRA realize that they had gone too far, and Adams publicly condemned it for undermining the "legality of the use of force". Since then, the strategy of Republicans has changed.

Turning point: beating all parties while talkingSecret talks

On January 11th, 1988, John Hume, the chairman of the Social Democratic Labor Party (SDLP), who has always advocated autonomy but is relatively neutral, held a secret meeting with Adams for the first time to discuss the possibility of letting IRA cease fire.

The meeting was a turning point in the Northern Ireland conflict and provided an opportunity for future peace talks. In 1989, Adams announced that he wanted a "non-military political movement for self-government". A few months later, the Secretary-General of Northern Ireland admitted that Britain could not defeat IRA completely by force, and it was necessary to negotiate with Sinn Fein and other political means to resolve the conflict. Secret talks between various parties have come and gone, and the British government has also had a direct dialogue with IRA, which was brokered by the British Intelligence Agency. Moreover, the British government has made it clear that if most citizens in Northern Ireland agree to reunification with Ireland, the British government will respect citizens’ choices. In 1992, Irish Prime Minister Albert Reynolds, without knowing that the British government had secretly contacted IRA, also asked his senior officials to secretly contact Sinn Fein. The two governments reached the same goal by different routes and finally reached the same node. In April 1993, after many secret talks, Hume and Adams issued a joint statement: Irish citizens should have the right to decide where they belong. On December 15, 1993, Major and Irish Prime Minister Reynolds issued the Downing Street Statement, accepting the principle of self-determination in Northern Ireland, provided that all Irish citizens (including the south and the north) agree.

While talking and fighting, the violence never stopped. Let me cite two examples: in October 1993, IRA exploded in a fish shop on Shankill Road, a royalist gathering area, killing ten people. After that, the royalists retaliated by assassinating two Catholics. On October 30th, UFF killed eight people and injured 13 others at a Halloween party in the Greysteel bar in the Catholic community. Revenge for revenge, Northern Ireland is still full of blood.

Pusher: American intervention in Clinton’s visit to Northern Ireland

In May 1995, Sinn Fein and the British government met formally for the first time. In November of the same year, Clinton visited Northern Ireland and sent George Mitchell, a Democratic politician, as the special envoy for Northern Ireland to act as a middleman for the negotiations. Negotiations finally started, but in February 1996, IRA thought that the London government’s demand for their disarmament was not keeping its promise, so it announced the suspension of the ceasefire and exploded in London’s financial district. Although they gave a warning 90 minutes in advance, two people still died, resulting in a loss of 100 million pounds. This event ended the 17-month ceasefire agreement. In June of that year, IRA exploded in Manchester City, destroying a large area in the center of Manchester City. IRA bombings occurred one after another in Britain. Royalist parties once again reiterated the importance of disarmament before negotiations. Sinn Fein was driven out of the negotiating table, and several other political parties and the British and Irish governments continued peace talks. However, the talks were not smooth, and no agreement could be reached on some simple issues, such as whether Mitchell should be the chairman, so the talks were suspended.

Turning point: Blair took office to restart negotiations and sign an agreement

On April 10th, 1998, Easter Good Friday, the negotiations finally came to fruition, and the parties signed the famous Good Friday Agreement. There are five main points in the Agreement: First, the future and constitutional status of Northern Ireland will be decided by its citizens; Second, if the majority of citizens in the north and south want a unified Republic of Ireland, they can obey the majority opinion through elections; Third, Northern Ireland’s current constitutional status remains in the United Kingdom; Fourth, citizens in Northern Ireland have the right to define whether they are Irish, British or both. Fifth, the Republic of Ireland will give up its claim to the territory of Northern Ireland, and the demands of all citizens will be protected by the Constitution. The agreement agreed to establish a Northern Ireland House with decentralized power and shared management rights, and to reform the police, hoping (but not insisting) that both armed groups would disarm.

All families in Ireland received an agreement, and on May 22nd, Northern and Southern Ireland held a referendum on the agreement. Seventy-one percent of Northern Irish people supported the agreement, including all Republicans, and royalists supported and opposed it equally. In Ireland, 94% of the citizens voted for it. In the definition of history textbooks, this is also the end of "Troubles".

Stalemate: The conflict continues to disarm weapons such as toothpaste.

From 1998 to 2003, it was the stage of trying to implement the Good Friday Agreement. It is difficult to negotiate the agreement, and it is even more difficult to implement it.

Shortly after the signing of the agreement, some extreme IRA members who were dissatisfied with Sinn Fein separated and established the "Real IRA". Conflicts continue in the streets of Northern Ireland, and the "real Republican Army" continues to carry out explosive activities. For example, on August 15th, they detonated a bomb in the center of Omagh, killing 29 people and injuring hundreds. Adams publicly condemned the violence and called for it to become history. On September 3, Clinton visited Northern Ireland for the second time, hoping to advance the peace process. On September 10th, Adams met with David Trimble, the 12th president of UUP, which was the first formal meeting between Republicans and royalists in 75 years. At the same time, the British government also began to withdraw troops, reform the police, release prisoners, and remove isolated roadblocks and buildings.

In October of the same year, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Xiumo of SDLP and Trumbu of UPP for their contributions to the Irish peace process. Historically, this Nobel Prize was awarded too early, because the most important issue of disarmament has not yet reached an agreement with IRA, and it is difficult to negotiate the decentralization and sharing of the Northern Ireland government under the threat of a gun. The IRA’s disarmament was delayed again and again. One year after the signing of the agreement, there was still no progress in the formation of the government. The American special envoy Mitchell was once again invited back to mediate. In November 1999, the Irish Republican Army agreed to contact and talk with the Independent International Commission on Disarmament. On December 2, the Northern Ireland government was established, with Trumbu as the first minister of Northern Ireland and Martin McGuinness of Sinn Fein as the minister of education. The Northern Ireland government began to negotiate with London on the specific issues of decentralization.

In October, 2002, the British government stopped the Northern Ireland government again. First, there was no movement when IRA disarmed. Second, it was discovered that IRA spy network was monitoring the Irish Parliament. Later, this spy case failed to be established. More intricately, Denis Donaldson, a senior official in the spy network, turned out to be an undercover sent by British intelligence agencies and had worked for Britain for more than 20 years (who was assassinated in April, 2006). The revocation of the Irish government’s management license this time is not just to scare them like the previous ones. The British government is serious, and it was not until 2007 that the Northern Ireland government was restored.

During this period, the negotiations on decentralization and sharing went on and on, and IRA disarmed weapons in batches several times, but all of them were like squeezing toothpaste. The royalists asked for photos as evidence, and IRA refused to provide them. Moreover, armed conflicts on the streets of Northern Ireland also occur from time to time, and the estrangement and hatred between neighbors are still on the verge. In February, 2005, IRA announced that it would withdraw its promise of total disarmament. Seeing that the peace process was about to go backwards again, Adams publicly called on IRA to keep its promise. Although Sinn Fein always denied its relationship with the IRA, Adams was still listened to. In October, the inspector of the Independent Disarmament Commission announced that he was satisfied with IRA’s disarmament. At this time, IRA was completely renounced. The British government thinks this is a big step in the peace process, but the royalists remain skeptical because there is no photo evidence.

Epilogue: The anger and bitterness of co-governance are still there.

After years of conflict and estrangement, how can we make old enemies live in harmony? Compared with Blair’s many small moves, Mandela’s "truth and reconciliation" comprehensive Amnesty is more far-sighted and tolerant.